2LT Allan Ewoldt

Army Air Corps

1942-1943 WWII

Allan James Ewoldt was born on Dec. 5, 1916, in Cleghorn, but grew up on a farm near Hartley. He was third in a family of six children: Sylvan, Leonard, Charles, Margery, and Erma. Ewoldt attended rural schools through the sixth grade (1931), when he left Center Township No. 1 in O’Brien County for Hartley High School. He graduated in 1935, the same year his parents moved from their farm southwest of Hartley to an acreage on the edge of town. He continued to help his father farm, even after entering Iowa State College.

Ewoldt was a student at Iowa State College from Winter Quarter 1939 through Fall Quarter 1941, entering in pre-veterinary medicine, later changing to major in science and then zoology. In 1940, Ewoldt registered for the Selective Service. When he enlisted at Ft. Des Moines on Feb. 20, 1942, Ewoldt was 25 years old and classified as a sophomore at Iowa State. He completed his training by July 27 in California at Oxnard and at Taft Field. An aviation cadet, he graduated on Sept. 29, 1942, at Roswell Army Flying School (New Mexico) with Army Air Corps Class number 42-1 as a second lieutenant.

He was stationed in North Africa with the 348th Squadron, 99th Bomb Group. The 99th came to be referred to as the “Diamondbacks” due to a diamond insignia painted on the vertical stabilizer of their B-17s. In January 1943, with the end of the North African Campaign in Tunisia in sight, U.S. and British political and military leaders met at the Casablanca Conference to discuss future strategy. The British persuaded the Americans to agree to a Sicilian invasion because removal of Axis air and naval forces from the island would open the Mediterranean and save Allied shipping. Code named Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily was a major campaign of World War II. The Allies took Sicily from Italy and Nazi Germany in a large-scale amphibious and airborne operation, followed by six weeks of land combat. When Axis forces had been defeated in Tunisia, Ewoldt's Allied strategic bomber force began attacking industrial targets in southern Italy, the ports of Sardinia, and the principal airfields of Sardinia, Sicily and southern Italy.

In a June 17, 1943, letter from home, Allan’s mother wrote that they had heard his name on the radio: “Well, we needn’t wonder for once what you were doing. We heard your name on the noon news in connection with the raid on Sicily … The news said two hundred Flying Fortresses roared over Sicily and I supposed you were in one of them. You had better look out for me if you get reckless — a good day’s work is all right but no tricks.”

Ewoldt was recognized for bravery in those air raids in June. Beginning July 3, the bombing attacks focused on Sicilian airfields and Axis communications centers with Italy. During a July 5 attack by 27 U.S. bombers on the Sicilian airfield at Gerbini, 2nd Lt. Allan Ewoldt played a key role. He was co-pilot of the B17 Flying Fortress nick-named Dee Zip Zip. It was his 33rd mission — all focused on the campaign in Sicily and Italy — in just three-and-a-half months.

The Army’s newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, reported the story of the July 5th mission as told by two of the plane’s gunners, Technical Sgt. David Fleming and 1st Sgt. Allen Huckabee. In vivid detail, they conveyed the story of the battle of a single damaged Flying Fortress against a swarm of at least 35 Messerschmitt 109s and Macchi 202s. Ewoldt’s bomber was one of the last three planes in the second wave of the formation, flying at the lowest altitude and more vulnerable to enemy fire. His B-17 was 10 minutes from its target when the first enemy fighters appeared. Eventually, their anti-aircraft fire knocked out Ewoldt's No. 4 engine, cutting down the plane’s speed. The entire formation cut its speed to match and sheltered the Dee Zip Zip until it regained altitude. Then the No. 1 engine went out. The bomber was flying at barely more than stalling speed. The formation's only option was to abandon the crippled aircraft. Immediately, Italian and German fighters swarmed in for the kill.

“It sounded like rice on a tin roof,” Fleming told the Stars and Stripes, “when bullets began to hit us. The radio went out, then the oxygen, then the men.” But the bomber continued to fly and fly, despite holes in the wings and fuselage big enough to crawl through. The pilot struggled to save the plane with the co-pilot Ewoldt slumped against him. Fleming went forward to help but found that Ewoldt had died, along with four other crew members. “Things were getting black,” Fleming said. “We were losing altitude fast. The pilot gave the order to abandon ship." Four crew members jumped, then the pilot, who thought he was the last one out. But Huckabee and Fleming remained, scarcely making it out a different opening. As they floated down, they watched the Dee Zip Zip keep flying, then eventually spin out of control and catch fire. The seven survivors and the damaged plane with Ewoldt and the other causalities came down about 12 miles from Ragusa, Sicily.

During this raid, the 99th lost three B17s but destroyed 70 enemy fighter planes on the ground and in the air. They severely damaged hangars, fuel supplies and ammunition dumps, resulting in a serious blow to the defenses of Sicily. For their bravery in this dangerous but successful mission, the Dee Zip Zip and the 99th Bombardment group received a Citation from the Major General of the 15th Air Force.

When Operation Husky started four days later on July 9, only two Sicilian airfields remained fully serviceable and more than half the Axis aircraft had been forced off the island. By Aug. 17, the Allied invasion had achieved its goals: Axis air, land and naval forces were driven from the island; the Mediterranean's sea lanes were opened; and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was toppled from power. Operation Husky opened the way to the Allied invasion of Italy —and ultimately — the end of the war.

Ewoldt and the other casualties from his crew were buried in Scicli, near Ragusa, and then re-interred in the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis in 1949.

Lieutenant Ewoldt received four ribbons for distinguished service and the Distinguished Flying Cross — the highest medal awarded to servicemen after the Medal of Honor.

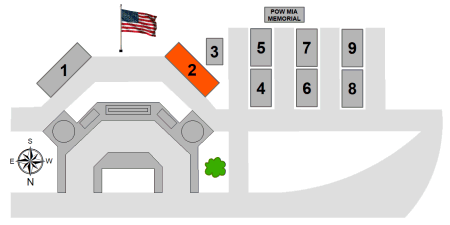

Locator